Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron

The Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron in Shropshire is one of the ten museums that make up the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site.

It was from Coalbrookdale Ironworks back in the early eighteenth century that a significant development in the production of pig iron was made by Abraham Darby I. Rather than fuelling his blast furnace with charcoal, which was expensive and in limited supply, he used coke, a form of coal which was local, cheap, and plentiful.

This change in procedure reduced the cost of iron and increased its applications and is thought to be the spark that ignited the industrial revolution.

The Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron connects the change in iron processing with the industrial revolution. It is a “must” to spend as much time here to fully understand the events that took place within the Ironbridge Gorge and their effect on all industry.

Being a material scientist, but not a metallurgist, I found some of the terminology hard to understand, and the amazing remains within the museum and around the gorge did baffle me some.

Mass production, and the chance to own and use modern, desirable products, is nothing new to most of us. But that drive to produce more and cheaper, to make products that could be offered to a larger market started here, in Coalbrookdale.

I’ve spent many years in a manufacturing environment and understand how much effort it takes to manufacture a product at much lower cost. So you’ll have to trust me when I say this is a truly exciting area to explore. The Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron explains the determination and effort made by the people of yesteryear, and displays their furnaces and some their products, the most famous being the Ironbridge.

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron - Abraham Darby I

Abraham Darby lived a short life, but during his life he made a large contribution to the advancement in the procedures used to manufacture metals. Born in April 1678, Abraham Darby already had iron smelting in the family as his great grandmothers brother, Dud Dudley had already tried, unsuccessfully, to smelt iron without charcoal.

His metallurgy career started in the early 1690s as an apprentice in Birmingham where brass mills were made to grind malt. It would have been from the brewers he met that he learnt how they used coke in their malting ovens rather than coal so as not to contaminate the malt with sulphur.

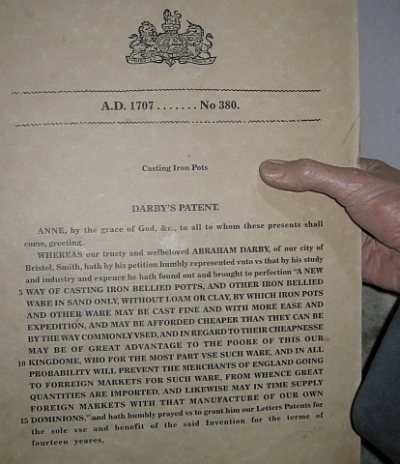

Abraham Darby I Patent

Abraham Darby I Patent © essentially-england.com

In 1699 he married Mary Segeant and they moved to Bristol where he continued working in a brass foundry and developed ways to mass produce brass pots using novel sand moulds.

The new moulding technique allowed thinner and hence lighter pots to be made. By 1705 he had moved into iron casting, and held a patent for casting iron pots. These pots became very popular and examples are displayed in the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron.

It was in 1708, whilst working for a brass foundry in Coalbrookdale that he leased a blast furnace in the same town and started experimenting with different coals to make pig iron for casting. The outcome from these experiments led to the use of coke rather than sulphur containing coal to fuel the blast furnace.

His surviving account book for the first year shows that 81 tons of iron products were sold during that time, and he decided to leave the brass foundry to concentrate on his own iron foundry business.

The business went from strength to strength and the construction of another, more productive blast furnace was started around 1715. However, Abraham Darby never saw this furnace in operations as he died in 1717.

The blast furnace used by Abraham Darby I has been excavated and is part of the exhibits in the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron.

Coalbrookdale Cast Iron Pot © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Cast Iron Pot © essentially-england.com Coalbrookdale Cast Iron Pot © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Cast Iron Pot © essentially-england.comIron Making

At this point we need to deviate a little, since some technical background is required to understand what happened in Coalbrookdale over 300 years ago and why it's such a big thing. So let's take a quick look at how iron is made, and I’ll do my best to keep it simple!

By mass iron is the fourth most abundant element on earth. It has the chemical symbol of Fe from the Latin ferrum. Pure iron is a soft metal and reacts quickly with oxygen and water to form iron oxides and/or rust. By adding small quantities of other materials, iron can be made stronger. Steel, for example, is around 1000 times harder than pure iron.

Pig Iron

Pig iron is the crude product that forms when iron ore is melted in a blast furnace with coke or charcoal and limestone. The resulting iron has a carbon content of 3–5%, contains some silicon, is rather brittle and has limited uses. It is usually formed into easy-to-handle ingots that are transportable and suitable for re-melting.

Cast Iron

In simple terms cast iron is iron that has been melted and poured into a mould or cast, and allowed to cool. Its chemical composition will include 2-4% carbon plus small quantities of silicon and manganese. Often there are also sulphur and phosphorous impurities. So it looks like the early cast iron could have been made straight from molten pig iron. It is a hard, brittle material that cannot be heated and have its shape changed. One good feature is its compressive strength, and it was much used by the early construction industry. Ironbridge was the first bridge in the world that was constructed from cast iron parts.

Cast Iron Deerhound Table Designed for the 1855 Paris International Exhibition © essentially-england.com

Cast Iron Deerhound Table Designed for the 1855 Paris International Exhibition © essentially-england.com

Wrought Iron

Wrought iron is iron that can be heated without melting it all the way. The softened material can then be worked with tools, like a blacksmith would do. The term “wrought” is actually derived from the past participle of “work”. It is a very low carbon content iron, having less than around 0.08%, but does contain 1-2% “slag” which is a byproduct from the smelting process in the blast furnace. The slag will contain sulphur, phosphorous, and silicon, calcium, magnesium, and aluminium oxides.

Pig iron would have to go through a refining process to reduce the carbon content in order to make wrought iron.

Wrought iron is more flexible than cast iron and will distort rather than shatter, as the more brittle pig iron and cast iron will.

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Coke versus Charcoal

Charcoal is produced by heating wood in

an oxygen free environment to remove water and other volatile products.

Although this produces a good source of relatively impurity free fuel it does

require trees, and these need time to grow. In England there were not enough trees

to fuel the industrial revolution, so iron manufacturers looked at the much more plentiful coal.

Unfortunately coal contains sulphur, which isn't very desirable when trying to make good quality iron. Coke was made by heating coal in an oxygen free environment.

Blast Furnace

This is where the clever stuff is done. Looking at the excavated brick lined furnace remains around the Ironbridge World Heritage site, it all looks so simple: pour iron ore, coke or charcoal, and some limestone into the top of a furnace and you get pig iron at the bottom. However, there is a lot of chemistry required to get this correct and it goes something like this…

Top of the Blast Furnace at the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

Top of the Blast Furnace at the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.comAll materials added to the furnace are crushed to approximately hand-sized pellets. High iron content iron ore such as Hematite (Fe2O3) or Magnetite

(Fe3O4) is used to make the iron, while the limestone helps to remove unwanted impurities like sulphur.

The iron ore, coke or charcoal, and limestone are mixed in the correct quantities and poured into the top of the blast furnace. The furnace is a huge melting pot through which the solid materials will descend and gases rise.

The iron ore goes through a number of reactions to remove the oxygen:

At 455°C 3Fe2O3 + CO → CO2 + 2Fe3O4

At 590°C Fe3O4 + CO → CO2 + 3FeO

At 705°C FeO + CO → CO2 + Fe

FeO + C → CO + Fe

The coke or charcoal descends through the melt until it reaches the point at which the blast is introduced. This is powered by huge bellows, driven by a water wheel, which set the coke to burn and produce heat following the reaction:

C + O2 → CO2 + heat

But since this reaction takes place at high temperature and there is a high concentration of carbon, the carbon dioxide breaks down to carbon monoxide:

CO2 + C → 2CO

And it is the carbon monoxide that reacts to remove the oxide from the iron ore as in the chemical equations above.

The limestone also goes through a number of chemical reactions. The first starts at about 870°C

CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

The calcium oxide can then go on to remove impurities, for example sulphur,

FeS + CaO → FeO + CaS

Position of the Coalbrookdale Furnace Water Wheel

Position of the Coalbrookdale Furnace Water Wheel © essentially-england.com

The iron oxide then reacts with carbon as in one of the equations above, and the calcium sulphide will be part of the slag produced. The slag would also contain any aluminium, silicon, or magnesium oxides that are part of the iron ore or within the limestone.

Bottom of the Blast Furnace used by the Darby Family on display at the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron

Bottom of the Blast Furnace used by the Darby Family on display at the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron © essentially-england.com

The resultant molten pig iron descends to

the bottom of the furnace where it can be collected, while the lighter slag floats

on top of the iron.

This short BBC documentory explanes the iron making process and helps you understand how the Coalbrookdale Iron Works blast furnace would have worked.

Hopefully this page wasn't too technical!

I think it gives an introduction to this great museum, where outside but undercover you can discover the blast furnace. While inside you can find a great Georgian works building with its prominent clock tower, and see what craftsman did with iron. To find out more about the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron and the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site please visit their website here.

Are You Planning a Trip to Shropshire?

Shropshire is a marvellous place for history and food lovers! There's so much to see and do and taste, that you'll need more than just a short visit. If food is your thing, head to Ludlow and start exploring from there. For history lovers, Shrewsbury makes a great base with many historical sites in very easy reach.

Where You Could Stay

To see more self-catering cottages in Shropshire click here or check out holiday cottages in other parts of England by clicking here.

If you need to find a hotel, then try one of these search platforms...

What You Could See and Do

Here are a few places that should go on your must-see list:

- Wroxeter Roman City

- Shrewsbury Abbey

- Shrewsbury

- Attingham Hall and Parkland

- Cantlop Bridge

- Snailbeach Mine

- Much Wenlock

- Offa's Dyke

- Ironbridge Gorge, The Iron Bridge & Broseley Jitties

- Ludlow Castle

- Stokesay Castle

- Bridgnorth

Click here for a great list of things to do in Shropshire.

If you enjoyed reading about the Coalbrookdale Museum of Iron and would like to read more about the Ironbridge Gorge World Heritage Site please click here or if you want to find more things to do in Shropshire please click here.