The Norman Conquest

Nothing changed the face of England as comprehensively as the Norman Conquest. The Romans came, saw and left after a while. The Anglo-Saxons came and settled. The Normans arrived and turned England upside down.

They brought new laws, new rules and a new language. They changed the very landscape, building towering stone castles and heaven-storming cathedrals. They changed the way people lived, dressed and even what they ate.

But how did it all come about? Surely William did not just wake up one morning and decide to invade England? He certainly did not. And if you care to look you'll find that the roots of the Norman conquest go back ... years back.

The Final Years of Edward the Confessor

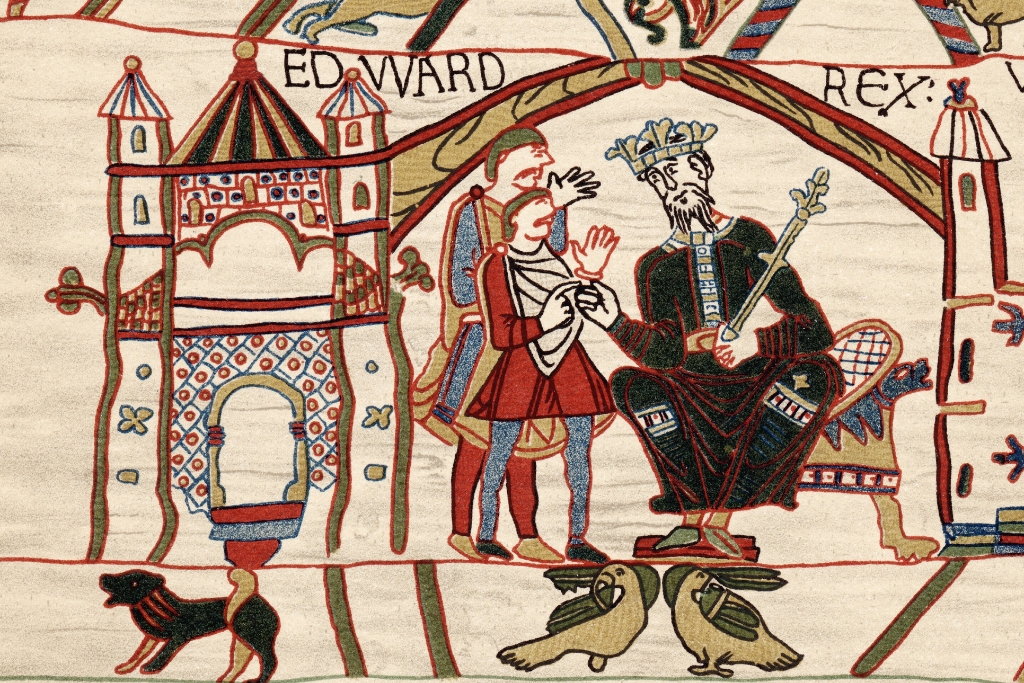

Edward the Confessor Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry

Edward the Confessor Scene from the Bayeux Tapestry © Photos.com | canva.com

Edward the Confessor had married Edith, daughter of Earl Godwin and sister to Harold of Wessex, on January 23rd 1045. She was fifteen years younger than Edward, but despite this the couple had no children. Rumour had it that Edward's mind was so turned towards Christ and the afterlife that he refused to consummate the marriage and rather concentrated on building Westminster Abbey.

In his final years, Edward the Confessor - now the last of the royal house of Wessex - began to worry about the succession. The Bayeux tapestry tells us that he promised the throne to his cousin William of Normandy, sending his brother-in-law Harold, Earl of Wessex, to William with the offer.

Harold was ship-wrecked on the way and rescued by William.

Grateful to be alive - and maybe seeing his deliverance as a sign from the Almighty - Harold, who was a very powerful man in his own right, is supposed to have sworn fealty to William. An oath he was about to break when he assumed the crown after Edward's death.

Contenders for a Vacant Throne

Edward the Confessor spent the last 15 years of his life, and a large part of his income, building Westminster Abbey. But when the abbey came to be consecrated on December 28th 1065, the king was too ill even to attend the service. Only eight days later, on January 5th 1066, Edward the Confessor died. His was the first burial in the new abbey - but it was also the end of an era.

Harold, Earl of Wessex, wasted no time. He had himself elected king within hours of Edward's funeral and - equally speedily - was crowned by Ealdred, Archbishop of York. The brand-new abbey that had just seen its first burial, now hosted its first coronation. The only remaining question was: would William of Normandy accept what had happened?

Of course, he did not. William, who had clawed his way to ruling the duchy of Normandy from the most inauspicious beginnings, was not going to let the richest prize in Europe slip through his hands!

Logistics of an Invasion

All through the spring and summer of 1066, William worked hard. Considering England his rightful heirloom, he made sure he had the goodwill of other European rulers and petitioned the pope for assistance. Fortunately, Pope Alexander thought his claim so good that he granted William a papal banner to fly over his army. And while engaged with all this diplomacy, William also built a fleet.

William assembled close to 700 ships at Caen, ready to set sail for England. 5000 foot soldiers, Normans and foreign mercenaries both, and 2000 cavalry, the cream of the Norman knights, had followed his call. To ensure the success of his enterprise, and to show his determination, William and his wife Matilda offered their seven-year-old daughter Cecily to a nunnery, the abbey of La Trinite at Caen. Then, all William had to do was wait for the right weather. But for weeks on end, the wind blew from the north.

Two Foes - one King

Harold, meanwhile, had assembled the largest army and fleet that England had ever seen. Harold's household troops and those of his earls, augmented by the national militia, the fyrd, awaited the Normans on the south coast of England. Summer wore on, supplies were running out and the men wanted to go home to see to their harvests. Finally, Harold agreed to send his men home and returned to London with his household troops. The ships were to meet him there, but many of them were destroyed in a sudden storm. William's fleet, departing from Caen, was caught in the same storm and driven up the coast to the mouth of the river Somme, bringing him ever closer to the English coast.

But while the Norman invasion fleet was kept close to the French coast by persistent northerly winds, the attempt by Norwegian king Harald Hardrada to claim the English throne was proceeding apace. With the northerly wind, King Harald sailed across the North Sea and landed in Northumbria. Here he burned Scarborough and then moved towards York, destroying towns and villages as he went. On September 20th, Harald Hardrada's army was intercepted by the forces of earls Edwin and Morcar who "gathered from their earldoms as great a force as they could get, and fought with that raiding-army and made a great slaughter" (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Worcester MS).

The slaughter at Fulford may have been great, but the English eventually lost the battle and many were killed. Harold, meanwhile, raced north as fast as he could, gathering forces along the way. After only four days on the road he arrived at York and surprised the Norwegian invaders at Stamford Bridge. Harold of England defeated the Norwegian king in a fiercely fought battle. It was said that of the three hundred ships Harald used to bring his troops to England, only twenty-four were needed to return the survivors.

So Harold of England had seen off one would-be invader. But the very next day, the wind changed and for the first time in weeks, it began to blow from the south. And on the French coast, William's fleet set sail for England.

William's Hour

On September 28th 1066 William of Normandy landed in Pevensey to

begin the Norman conquest of England. Harold and his men were 250 miles

away in the north, having just fought and won one of the bloodiest

battles in English history. As far as William was concerned, England was

his for the taking.

But Harold did not give up easily. He

rushed south, calling up the levies as he went. When he reached

Hastings, he may have had as many as 7,000 men, mainly infantry, no

cavalry and few archers. Harold drew up his forces along the crest of

the ridge, blocking the road to London. William's men comprised three

divisions. Each had archers, foot soldiers and a contingent of armoured

knights.

Harold Falls

Harold FallsFrom a Bayeux Tapestry Representation at Battle Abbey

© essentially-england.com

The battle between Harold's Englishmen and the Norman invaders was a closely fought contest. For hour after hour, the Normans battered the English shield wall, unable to break through. For a time, it even looked as if Harold might prevail.

But then, a setback turned into a lifeline for the Normans. The Breton line broke and men turned and fled. Caught up in the fight, the English shield wall opened and men began to stream down the hill, giving chase. Harold, fighting in the front row of the centre shield wall could do nothing but swear and pray. But his prayers were not answered.

William, mounted, had seen the momentary disarray and reacted immediately, turning his cavalry upon the chasing English fighters. Surrounded, they were cut down, leaving Harold's right wing dangerously weakened. And still, Harold and his men stood firm. And still, the shield wall held.

But while Harold clung to established battle tactics, William varied his approach. He ordered his knights to pretend to flee, again inducing his opponents to break open their shield wall to give chase. And when the English began to push the Norman attackers down the slope they were holding, he instructed his archers to move as far forward as they could and send their arrows over the heads of the battling men, into the massed ranks of the Anglo-Saxons beyond.

All know what happened then: Harold died, hit in the eye by an arrow. The shield wall gave and wholesale slaughter followed.

The Norman Conquest as it Happened (Maybe)

If you like your history animated, you really must watch this! Using the Bayeux Tapestry as both guide and backdrop, art students at Goldsmiths College created this animated version of the Norman Conquest. And it's about as epic and gory as the real one must have been - only much shorter. But so very true to life...

A Christmas Coronation

On Christmas Day 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey, completing the Norman conquest of England.

Following the Anglo-Saxon custom of electing a king by 'declaration' those present loudly shouted the new king's name. His guards, stationed outside the abbey, suspected treachery and began setting fire to houses around the abbey.

The congregation rushed out of the abbey, except for the bishops, a few clergy and the new king, who was seen to be "trembling from head to foot."

So William's reign began. The first Norman castles had been built at Pevensey, shortly after William landed, and Hastings, soon after the battle. The land along the coast and around London had been devastated. London burned on Coronation day. But the Norman conquest of England was not yet complete.

William returned to Normandy six months after his coronation, but it took three years until his forces took Chester. And five more years of upheaval and rebellion would follow until the Normans had secured most of their English lands. Until his death twenty years later, William would never be entirely certain of the island real.

Want to learn more about the Norman kings and the effect the Norman conquest had on Anglo-Saxon England? Try the following pages: