The Bayeux Tapestry

Between Art and History

Embroidery is something I enjoy when it's cold outside, rain lashes the windows and I can sit snugly by the fire, with a cup of tea and some music. I embroider, because it's a peaceful activity that gives me pleasure. I've never really considered it artwork, nor thought of it as a way of keeping historical records.

But actually, it can be both.

And nowhere is this more apparent than in the Bayeux Tapestry. The original is a historical record of the Norman Conquest. It tells of the events leading up to and during that fateful year of 1066, when Anglo-Saxon England finally ceased to exist.

But, as art has done since time immemorial, it also shows us how people of the period lived: how they dressed, what they ate, how they travelled. We get a glimpse of ceremonies and rituals. We can learn about the weapons they used in battle and the tools they had for everyday tasks.

The original Bayeux Tapestry is, of course, a very fragile museum piece. And if you want to see it, you'll have to travel to France. Maybe that's why expert embroideress Annette Banks decided to recreate it for all of us to enjoy.

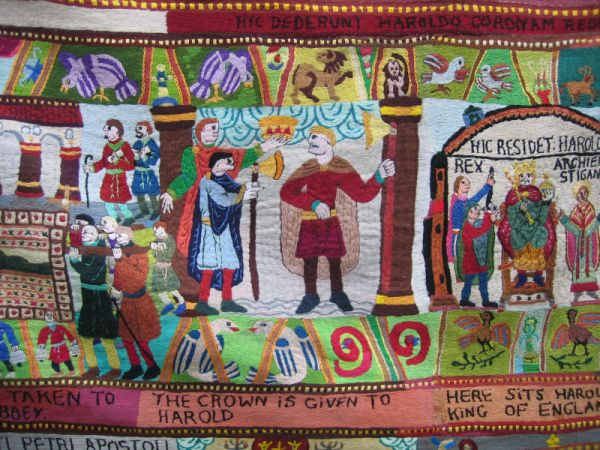

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold takes the crown © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold takes the crown © essentially-england.comIt's a project worthy of a huge team of dedicated embroiderers, very much like the way the original tapestry would have been made. But Annette Banks did it all by herself! She spent over 20 years on the project and she didn't just copy the original. Instead, she added her own interpretation, telling the story anew, this time in glorious colour.

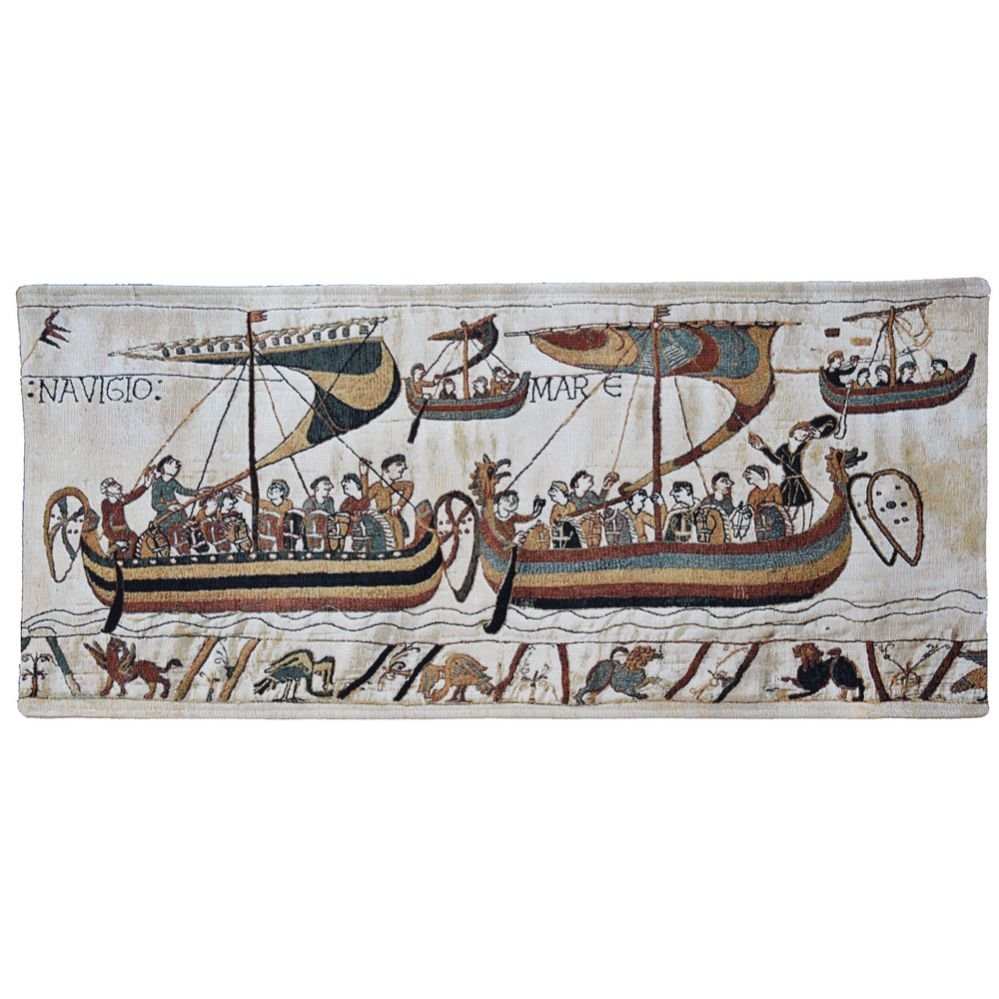

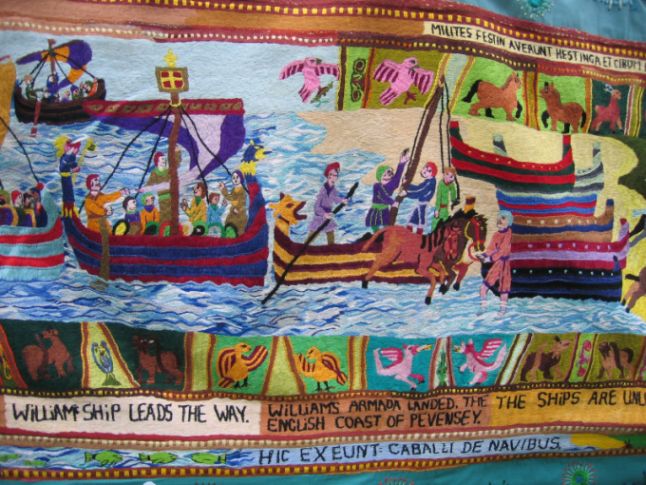

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, The invasion begins © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, The invasion begins © essentially-england.comAs soon as he realised that Harold has broken his vows, William of Normandy began to prepare his invasion fleet. This can't have been an easy undertaking, as most rulers in those days didn't own a fleet of ships or even a standing army. William had to build all of his, as well as gather troops willing to fight in a chancy enterprise in a foreign country.

But William was nothing if not stubborn, and - eventually - his invasion fleet left the French port of Barfleur, bound for England.

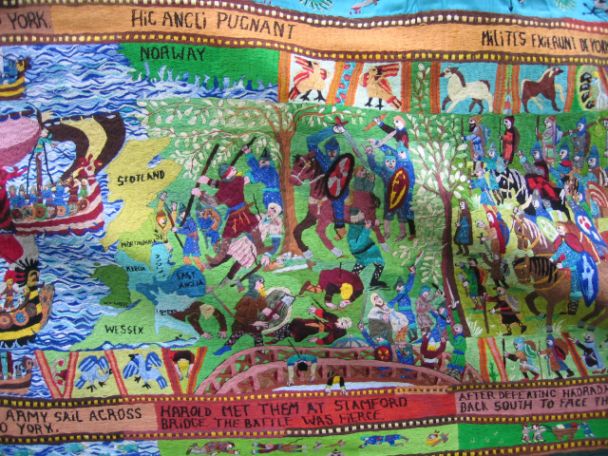

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold defeats the Viking Army © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold defeats the Viking Army © essentially-england.comHarold, who had waited beside the south coast for most of the summer for William to make his move, was now on the way north - with his entire army - to head off a second invasion of England. This one from his half-brother, Tostig, and Harald Hardrada, the king of Norway.

He intercepted them at Stamford Bridge on September 25th 1066 and - despite the long march north - defeated the Viking army in a decisive battle. Both Tostig and Harald Hardrada were killed.

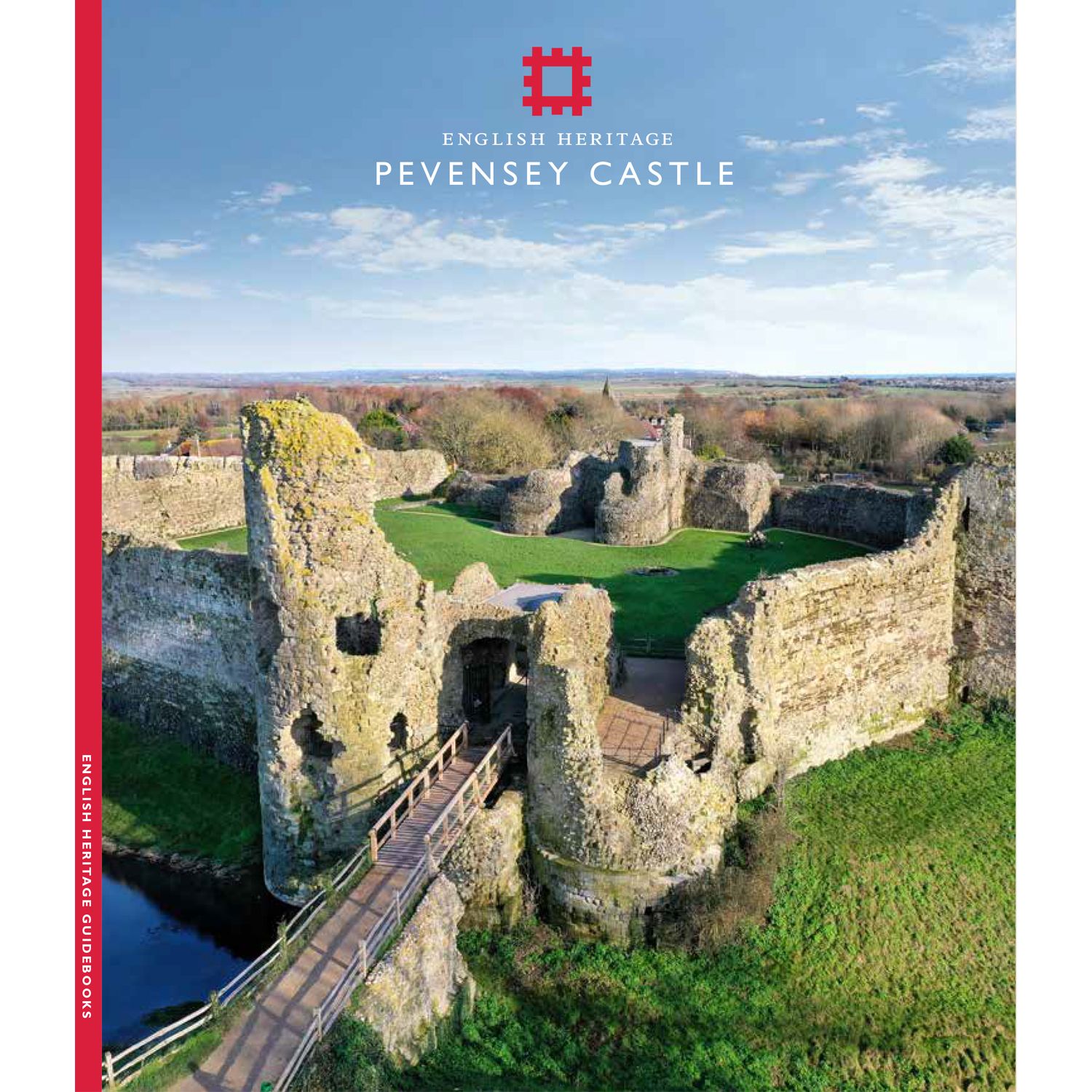

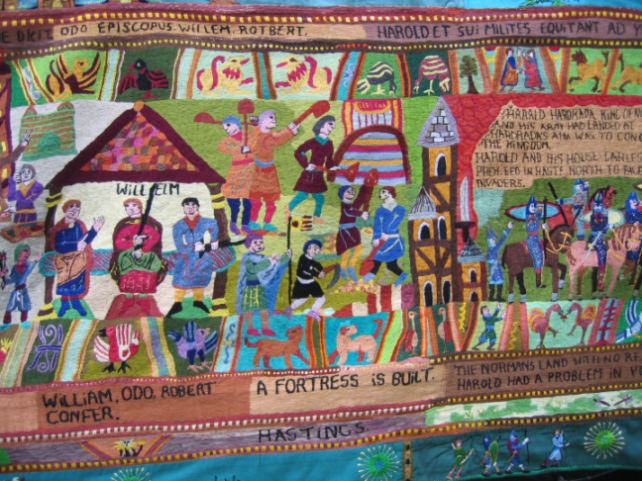

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, The Normans fortify the site of their landing © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, The Normans fortify the site of their landing © essentially-england.comMeanwhile, on September 28th, the Normans had landed on England's south coast, somewhere between Hastings and Pevensey, and spent their first days fortifying their encampment. As on the original Bayeux Tapestry, Annette Banks shows the Normans building a motte and bailey castle to keep their troops save from attacks.

A motte and bailey castle is - at the most basic level - a mound of earth, surrounded by a ditch and topped by a wooden palisade. Unless someone fires flaming arrows, William's troops would have been reasonably safe behind their impromptu fortifications.

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, the battle of Hastings begins © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, the battle of Hastings begins © essentially-england.comHarold's next move was a military feat worthy of Alexander the Great. Just days after a long march and a vicious battle, hearing that William had landed on the south coast, Harold and his army raced south again to beat back the second invasion.

They made it down to Hastings in days and set up camp on Senlac Hill, where they met William and his troops in battle on October 14th.

William and his army were clearly in an inferior position at the bottom of the hill. They were also outnumbered by Harold's men. But William had an ace up his sleeve: cavalry! The Anglo-Saxons used horses mainly as transport, fighting on foot in a tightly-packed shield wall.

Annette Banks' recreation of the Bayeux Tapestry clearly shows the Anglo-Saxon shield wall on the right of the panel, with the Normans on horseback before it.

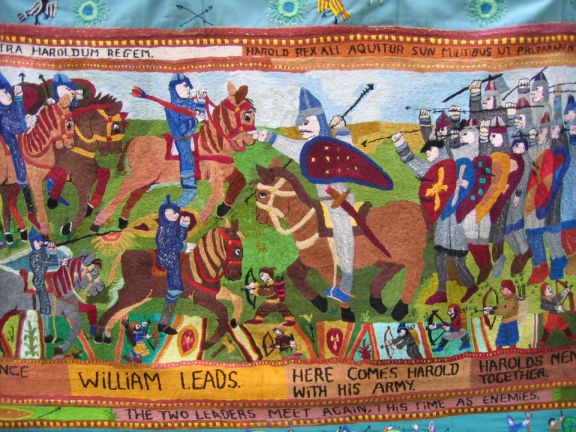

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold falls in the battle © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, Harold falls in the battle © essentially-england.comMost people who have heard of the Battle of Hastings also know what happens: The English shield wall stands firm for most of the day until the Norman duke instructs his cavalry to pretend to flee, enticing the English to open their fiercely defended shield wall. King Harold falls, maybe after being hit in the eye by an arrow.

And while there is now some debate over the arrow wound, the actual outcome of the battle is beyond debate.

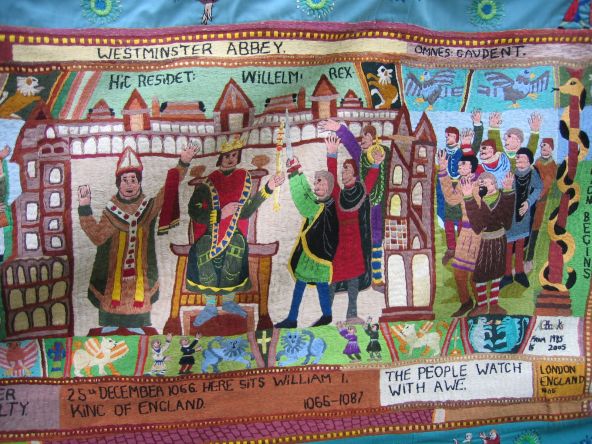

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, William is crowed King of England © essentially-england.com

Bayeux Tapestry by Annette Banks, William is crowed King of England © essentially-england.comSo William won England in battle, but it took him much more than a single battle to hold it. Not until Christmas Day 1066 was he established enough in his new kingdom to be crowned in Westminster Abbey.

And neither the original version of the Bayeux Tapestry, nor Annette Banks' colourful panels show how the whole occasion almost ended in bloodshed! (For anyone who wants to know: when William was proclaimed king, people inside the abbey started cheering as was the English custom. Norman troops stationed outside the abbey took this as a sign of English rebellion and started to set houses around the abbey on fire in retaliation. It took some time and effort to quell the ensuing chaos, I'm sure.)

And there you have it: the story of the Norman Conquest told again - this time by a modern version of the Bayeux Tapestry. I think it's a marvellous piece of work, totally doing justice to such an amazing event in English history. Annette Banks' dedication, discipline and perseverance are as stunning as her artistry and needlework skills. And I'm very grateful that I've had the opportunity to see her work during the celebrations for King Harold Day at Waltham Abbey.

If you'd like to hear Annette Banks talking about her reworking of the Bayeux Tapestry please watch this YouTube video.