Carlisle Castle

The Most Besieged Place in England

Carlisle Castle has defended Carlisle in Cumbria for centuries. As a border town between England and Scotland, Carlisle was a strategic stronghold and has been fought over for hundreds of years and switched from English to Scottish hands and back a again almost too many times to count. Carlisle Castle isn’t a romantic ruin. It's a fortress that has been in continuous use for almost 900 years, and its current structure reflects the modifications needed to cope with military advances over the centuries. Parts of the castle are out of bounds as they are still used as a storage facility by the army.

William Rufus, son of William the Conqueror, built the original Norman wooden motte and bailey castle in the late eleventh century on the site of a former Roman fort on Hadrians Wall. It was during the reign of King Henry I that a stone castle was constructed to replace the earlier Norman structure. Building of the medieval castle started around 1122, and shortly after, a stone city wall was also erected to defend Carlisle.

Carlisle Castle © essentially-england.com

Carlisle Castle © essentially-england.comCarlisle Castle History

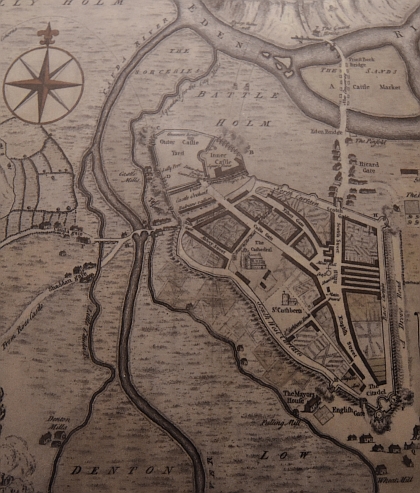

Map of Carlisle from Late Tudor Times (Photo taken of display in Carlisle Castle).

Map of Carlisle from Late Tudor Times (Photo taken of display in Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.com

English King Henry I started the construction of the stone-built Carlisle Castle, but it didn’t take long before it fell into Scottish hands.

The castle was still unfinished when King Henry I died in 1135. During the infighting between his heirs, Stephen and Matilda, King David I of Scotland took advantage and occupied the castle. He continued with the building work and controlled the castle until his death in 1153. His grandson, King Malcolm IV, held on to Carlisle Castle until 1157, when he lost it to the more powerful English King Henry II.

Henry II continued to strengthen Carlisle Castle and build himself some chambers and a chapel. It wasn’t long before the castle was under attack once more. In 1173 and 1174, King William the Lion - brother of Malcolm IV - attempted to re-take the castle by force, but failed in his endeavour.

King John of England continued to improve Carlisle Castle and used it as a base from which he and his followers oppressed the north of England. King John’s behaviour caused bitterness and outright revolt, and saw the English barons form an alliance with King Alexander II of Scotland. In 1216, the people of Carlisle opened the town to the Scots. Their army attacked and captured the castle, holding it until shortly after King John's death in October for 1216.

Artist Impression of the Early Medieval Carlisle Castle (Photo taken of display in Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.com

Artist Impression of the Early Medieval Carlisle Castle (Photo taken of display in Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.comIn the Treaty of York - signed in 1237 - the Scots agreed to give up their fight for the northern counties of England. This led to a peaceful period for most of the remaining thirteenth century.

Edward I did not realise his dreams of conquering Scotland. He died in 1307, and his son made a poor fist of continuing his father's military campaigns north of the border.

After winning a number of battles, the Scottish started to drive the English out of Scotland,

In 1315, King Robert Bruce besieged Carlisle for eleven days. Without the very wet weather - which left the moats full and the surrounding countryside muddy - Carlisle might have succumbed to the attack. But the saturated ground made it impossible for the Scots to use siege engines or try to undermine the castle walls, and their attempt to take Carlisle Castle was unsuccessful.

The Great Chamber within Carlisle Castle

The Great Chamber within Carlisle Castle © essentially-england.com

Fighting continued through the fourteenth century. Weaponry developed and by the 1380’s a small number of brass guns had been put in place at the castle. By the 1430’s the brass weapons had been replaced with six stronger iron cannons.

Defending the northern counties were the March wardens or Lords of the North. England's kings paid the March wardens handsome salaries and the wardens raised their own armies to protect northern England. Famous English families, such as the Percys and Nevilles, held positions as March wardens.

With a power base and a private army, the March wardens could bring danger to a king. It's not surprising, that many kings invested men they could trust as Lord of the North. King Edward IV chose his brother Richard, the Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III). Later, King Henry VII chose a local baron for the role, and the Dacre family held this position for many years.

The Tudor Half Moon Battery in Front of the Captain's Tower

The Tudor Half Moon Battery in Front of the Captain's Tower © essentially-engalnd.com

During the Tudor period, Carlisle Castle was modified and strengthened again.

In 1541 King Henry VIII was concerned about a coalition

between Scotland and France and had

the castle’s defences improved in order that the castle could withstand, and be

used for, heavy cannon fire. To this end the keep roof was lowered and strengthened,

new bulwarks and the half moon battery built, and the wall walk reinforced.

He also ordered the construction of a citadel at the southern point of the city wall.

Perhaps the most famous prisoner to be housed at Carlisle Castle was Mary, Queen of Scots.

In May 1585, Mary fled to England after a revolt in Scotland. She was held in what was called the Warden’s Tower, and the cost of running her court was covered by Queen Elizabeth and is quoted as being around £56 per week. Her captivity was not harsh and she was free to walk around the castle, but was carefully watched in case she tried to escape.

Queen Elizabeth didn’t trust Mary and after a few months she was moved to Bolton Castle in Yorkshire. For months, she was watched and moved regularly from secure place to secure place, never too close to the sea or London in case of escape. Eventually, in 1587 Queen Mary was executed for treason.

Queen Mary of Scotland (Photo taken from a display at Carlisle Castle).

Queen Mary of Scotland (Photo taken from a display at Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.com

By 1603 the amalgamation of the English and Scottish crowns resulted in peaceful times in the border lands. Queen Mary’s son was now King James I of England. In 1617, King James I lodged at Carlisle Castle, found that it needed work, but did nothing to renovate it since the castle now saw little use. By 1633, even the guns had been removed. There really was very little need for Carlisle Castle. That is until the Civil War.

King Charles I's

rule was not a happy one. Between his strong Catholic faith and his belief in the the Divine Right of Kings, he made himself thoroughly unpopular - until war broke out and the king's forces met the Parliamentarians in battle.

The Keep © essentially-england.com

The Keep © essentially-england.comThe Royalist faction held Carlisle Castle and re-armed it with three batteries of guns.

It didn’t see Civil War action until 1644, when - after the battle of Marston Moor on the 2nd July - northern England fell to Parliamentarian control.

In October that year, the Scottish Parliamentarians put Carlisle under siege, enclosing the city in a ring of guns and ditches with a plan to starve the city into submission.

The city of Carlisle survived the winter siege. In the spring of 1645, English Parliamentarians came to support the besiegers. Life in the besieged city was hard. All metal was seized from the people to stamp coins to pay the Royalist soldiers. Food was dreadfully short - to the point where horses, dogs and rats served as food. Yet Carlisle held fast until the 25th June when, three weeks after the Royalists lost the Battle of Naseby, Carlisle lost any hope of support.

The damage caused during the siege was repaired using stone from the nave of Carlisle Cathedral and Carlisle Castle was garrisoned by a neutral army.

The remainder of the seventeenth century was again peaceful around Carlisle. The castle guns were only used to celebrate royal birthdays or the arrival of important visitors and by the end of the century the army garrison had left.

During the peaceful interval the castle was looked after by a few veterans who lived in the city. On a number of occasions the castle was used to house prisoners.

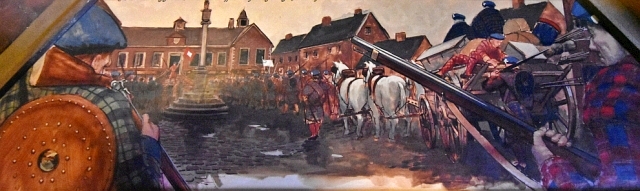

Artist Impression of the Jacobites in Carlisle (Photo taken from display at Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.com

Artist Impression of the Jacobites in Carlisle (Photo taken from display at Carlisle Castle). © essentially-england.comIt was a hundred years later when Carlisle Castle saw action again and this time it was a Jacobite rebellion led by Charles Edward Stewart (Bonnie Prince Charlie). The city had drummed up a militia of around 1250 men who, on the 9th November, faced around 5000 Scots. The city, and eventually, the army surrendered as they believed they had no chance against the savage Scots and on the 17th November Charles Edward Stewart entered the city preceded by 100 pipers. The majority of Scots left Carlisle to return to their homeland, leaving a garrison of 400 men to defend Carlisle.

Scottish occupation of the castle didn’t last long as the Duke of Cumberland’s army used heavy artillery to smash their way into the castle and the Scots surrendered on the 30th December.

The Duke continued with his aggression against the Scots and in the following April fought with them at Culloden.

The captured prisoners were taken to Carlisle Castle and kept in very cramped, dark, and harsh conditions. The cells were so full of men that some died and the cruel conditions have resulted in the “Licking Stones” where men licked stones to get moisture to stay alive. Of those men that did survive over thirty were hanged and most sent to North America.

Licking Stones © essentially-england.com

Licking Stones © essentially-england.comBy the end of the eighteenth century the castle was quiet and used mainly as a military store.

In the early nineteenth century, the threat of rebellious townsfolk gaining access to Carlisle Castle and the weapons stored within led to the return of a permanent military presence. So from around 1820 old buildings were modified and the castle converted to a barracks. The re-design included levelling the parade ground and filling in the half moon battery. By 1840 the barracks housed 250 people.

View Over the Parade Ground from the Inner Ward Walkway © essentially-england.com

View Over the Parade Ground from the Inner Ward Walkway © essentially-england.comAs the threat lessened towards the end of the century the castle was used as a training base for new recruits, and became the home of the Border Regiment until 1st October 1959. The castle played its part during the two World Wars, mainly as a storage depot and training centre. In the Second World War an anti-aircraft gun was mounted on the Keep roof.

Carlisle Castle Tour

You enter Carlisle Castle through the red sandstone-built outer gatehouse. It’s an impressive view as you walk up to it. The oldest parts of this structure are from around 1160, although it was heavily modified in the late fourteenth century. Initially it was the first of the castles defences, but had a number of different uses through the ages including being the sheriff of Cumberland’s office and exchequer, a barracks, and a sergeant’s mess. These varied uses have resulted in many modifications over the years.

The Outer Gatehouse © essentially-england.com

The Outer Gatehouse © essentially-england.com Room Inside the Outer Gatehouse © essentially-engalnd.com

Room Inside the Outer Gatehouse © essentially-engalnd.comFrom the outer gatehouse you enter the outer ward. As a medieval castle, this area would have had a barns and workshops, as well as grazing space for cattle. It’s amazing to think that this vast area has been raised a few feet in height and the ground levelled for use as a parade ground. This was done around 1820. The stone buildings are from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when the castle was a barracks and storage depot. The buildings are named after some of the battles in which the Border Regiment saw action. Some of these buildings are still in use and cannot be visited. One building that is well worth visiting is the Alma building which contains the Cumbria Museum of Military Life.

Cumbria Museum of Military Life © essentially-england.com

Cumbria Museum of Military Life © essentially-england.com Cumbria Museum of Military Life © essentially-england.com

Cumbria Museum of Military Life © essentially-england.comThe Tudor half-moon battery is a strange structure as it appears to be of no use as you cannot see anything out of it but the ditch in front of it. That is because the outer ward area was raised, and in fact covered the battery. Inside the battery is quite tight and it’s difficult to imagine thirteen men firing their guns from here. The smoke from the gun powder would have passed through a number of vents in the roof. With the noise, smoke, and the fear of being shot at, it couldn’t have been a pleasant place to fight in battle.

Inside the Half-Moon Battery at Carlisle Castle © essentially-england.com

Inside the Half-Moon Battery at Carlisle Castle © essentially-england.comThe Captains Tower or inner gatehouse stands immediately behind the half-moon battery. This part of the castle dates from the late twelve century when the inner ward was created. As most parts of the castle, it has been modified over the years.

The Inner Ward Side of the Captain's Tower

The Inner Ward Side of the Captain's Tower © essentially-england.com

This was the residence of the officer charged with the protection of the castle.

When first built, the half-moon battery would not have existed and there would have been a draw bridge over the moat, portcullis, and murder holes to navigate.

Take a close look at the architecture of the tower. The front is all designed for defence and lacks decoration, whereas at the rear in the living area of the medieval castle you’ll find that it is more decorated and stately.

It’s probably best to go up to the inner ward walkway first to get views of Carlisle and the surrounding countryside and a better overview of the inner ward buildings. The walkway completes a circuit of the inner ward and over the years has been widened and strengthened so that heavy cannons could be used.

View Over the Inner Ward

View Over the Inner Ward © essentially-england.com

View Over Carlisle from the Inner Ward Walkway

View Over Carlisle from the Inner Ward Walkway © essentially-england.com

Back at ground level in the inner ward, you’ll find the powder magazine from around 1827 that was designed to store up to 320 barrels of gunpowder. The next building along is the old militia store from 1881, from which uniforms and supplies were provided to soldiers. It now houses an exhibition on the history of Carlisle Castle. These two buildings are believed to stand on the site of a possible palace that was built for King Edward I. The only medieval remains of this palace are the shell of the great chamber. Although this building has been modified there are still some nice architectural features that demonstrate the early importance of the rooms within the chamber.

The Great Chamber © essentially-england.com

The Great Chamber © essentially-england.com Site of Queen Mary's Tower © essentially-england.com

Site of Queen Mary's Tower © essentially-england.comBeside, and connected to the great chamber, used to stand a tower. The tower was demolished in 1835 as its structure had become unsafe after centuries of neglect and its final use as a barracks. It was in this tower that Queen Mary of Scots was imprisoned.

Room Inside the Keep © essentially-england.com

Room Inside the Keep © essentially-england.com Room Inside the Keep © essentially-england.com

Room Inside the Keep © essentially-england.comIt is the keep, or great tower that is the most imposing structure within the castle. Its height was lowered in Tudor times to give the tower the strength to tolerate cannons being fired from the roof. Even so, it still stands at an impressive 21 metres tall. It is believed that before the palace was constructed by Edward I, that the Kings of England and Scotland would have entertained their guests in rooms within this tower.

Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.com

Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.com Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.com

Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.comIn a small corridor on the second floor of the keep are a collection of wonderful carvings and graffiti. Called The Prisoners’ Carvings, although there is no history of prisoners being kept in these rooms, these beautiful medieval carvings were skilfully produced. The style of dress and armour displayed in some of the carvings would suggest they date from the late fifteenth century.

Prisoner Carving's Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.com |

Prisoner Carving's Prisoner Carving's © essentially-england.com |

It is in the keep's groundfloor store rooms that you learn more of the horrors of Carlisle Castle. The vaulted rooms were designed for storage of food and drink, but sometimes they were used as dungeons. It is said that some prisoners were so tightly packed into one room and so poorly fed and watered that they licked the stone walls to get moisture. The resulting stones have unusual curved shapes and are called the “Licking Stones”.

Licking Stones Found in the Former Storerooms used to Imprison Jacobite Rebels © essentially-england.com

Licking Stones Found in the Former Storerooms used to Imprison Jacobite Rebels © essentially-england.comUnfortunately, there is no evidence of the Roman Hadrian’s Wall around the castle site. We recommend visiting the nearby Roman fort and wall remains to gain experience of the defences used over the last 2000 years to protect the borderland between England and Scotland.

Carlisle Castle is run by English Heritage. If you would like to know more about opening times and events please visit their website.

Holiday Cottages Around Carlisle

Or you could use Booking.com to search for accommodation.

If you have enjoyed reading about Carlisle Castle and would like to explore the city of Carlisle and its cathedral or other areas of England, then please use the links.